Inventories of their property made upon the deaths of Leonardo (d. 1612) and Girolama (d. 1622) show that there was no printing press in their home, only a worktable for cutting woodblocks. They do not seem to have owned a studio or workshop apart from their house across from the Trevi Fountain. Throughout their professional lives, they worked as image providers for associates like the printer Fachetti and the Oratorian publisher Jacopo Tornieri. It would have been in keeping with the family’s conception of a workshop for the two sisters-in-law to have worked together during the years when both of them were raising their many children. Girolama could expertly carve intricate images for botanical illustration as well as swirling, narrowly cut calligraphic tendrils that could survive the printing press, while Isabella knew how to invent and draw lace designs that visually incorporated and deconstructed floral and vine-like imagery.24 Leonardo was an experienced advisor for creating printed model books and seeing publications through the maze of contracts, legal associations, finances, and official clearances they entailed, and Rosato’s experience as a decorative painter meant that he understood that patterns advertised for lace-making were equally useful to the work of wall painters, embroiderers, portrait painters, and even gardeners. The lively, courteous address in Isabella’s dedication to an actual or aspirational patron likely transcended the comportment of clog-makers and similar artisans, offering a window onto the education and social class of the convent’s wards and the patronage devout noblewomen practiced at religious houses for girls.25 In this way, Rosato’s marriage to Isabella doubled the number of talented women in the family, bringing new skills and manners to the woodcarvers and broadening their production in the model book sector.

All of Isabella’s pattern books bore unadorned title pages except for the last one, Teatro delle Nobili et Virtuose Donne (1616), which featured an elaborate ornamental frontispiece engraved by academician and fellow printmaker Francesco Villamena. This is the work of hers that Baglione cited in his vita. As Leonardo is burnished by association with Antonio Tempesta, and Bernardino with Giuseppe Cesari, Isabella is linked with the skillful male woodcarver Giovan Giorgio Nuvolstella and the academician Francesco Villamena. The somewhat thin story of Parasole artistic accomplishment that emerges is strengthened by framing it in a garland of praiseworthy popes, significant physicians, renowned scholars, and major participants at the Accademia di San Luca.

We have bracketed a description of Girolama’s career and her fame, such as it was, between two primary sources, neither of which actually name her. The instances of her signed work constitute a very short list. Three books include woodcut illustrations bearing her monogram:

-

Dialoghi…intorno alle medaglie inscrittioni et altre antichità, 1592.26 The book is illustrated throughout with unsigned images of coins, including the inscriptions, which are the subject of the book. Only four images are signed, bearing the monograms of Girolama (under an image of the Arch of Titus), Leonardo, and Paul Maupin. The monogrammed full-page woodcuts show inscription-bearing Roman arches in an urban setting. Unlike the images of coins, they demonstrate the use of perspective, shading and atmospheric effects, architectural ornament, and figures. No inventor for these images is named, although some are clearly copies of well-known prints by Nicolas Beatrizet and others.

-

De SS. martyrvm crvciatibvs, 1594. This is a smaller-format Latin version, with woodcuts designed by Giovanni Guerra, of an Italian volume illustrated with etchings by Antonio Tempesta of tortures and martyrdoms of Catholic saints.27

-

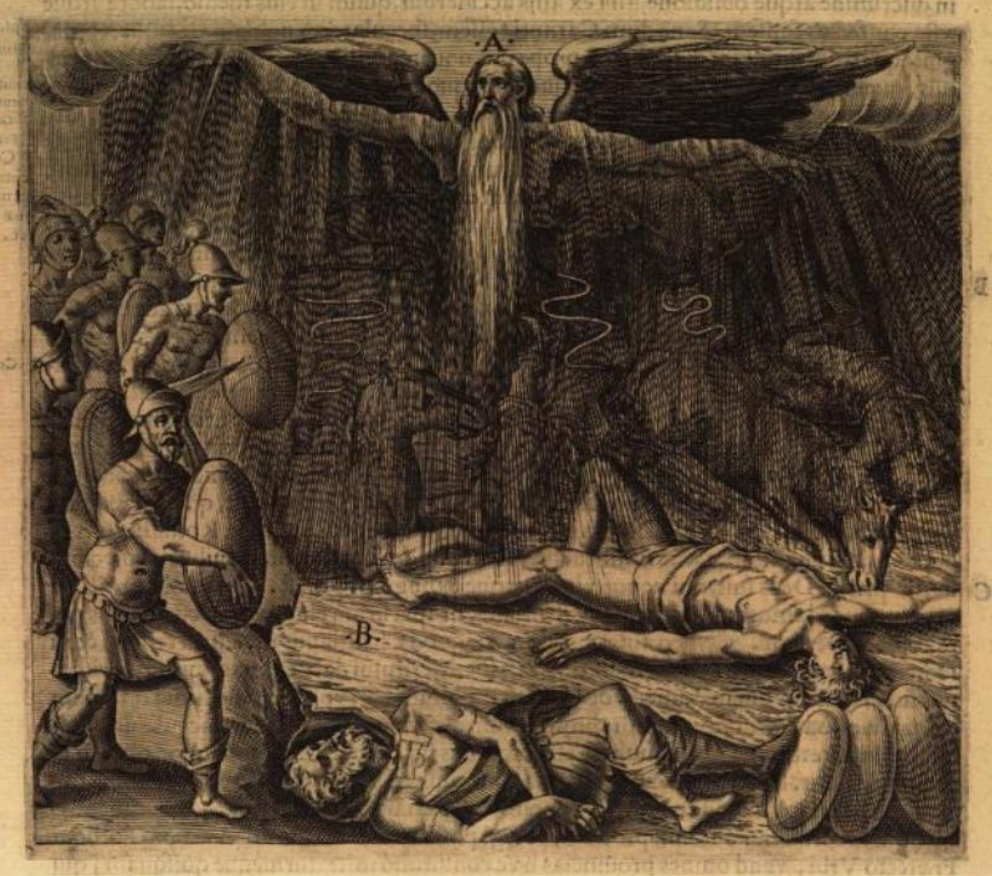

Annales Ecclestiastici, 1594. Most images in these volumes are of coins, as in Antonio Agustín’s dialogue, none of which are signed, but the publisher’s records show that Leonardo was paid a scudo apiece for images of coins during this period. He also received eight scudi in payment for a woodcut of Giove Pluvio, inspired by a famous scene on the column of Marcus Aurelius, that bears Girolama’s monogram.28 Although it could be assumed, this provides evidence that contracts for Girolama’s work were enacted in Leonardo’s name. 29 The image, small enough to have been cut from the boxwood that was a specialty of the family, differs completely from an earlier version of the same volume printed in 1590 that was deemed unsatisfactory (figs. 2.4–2.6). Capitalizing on her skill in cutting dramatic white forms snaking across dark backgrounds, Girolama emphasizes the thunder and lightning that accompany the god, whose miraculous appearance brings life-giving rain. She skillfully works chiaroscuro effects into the image so that there is a sense of depth in the shadow behind the god, from which soldiers and horses tumble to their deaths. In the foreground, a pathetic figure lifted from ancient Niobid or Amazonomachy reliefs, perhaps by way of printed battle scenes like Marco Dente’s, lies crumpled and foreshortened in the swirling water, his head resting against one bent arm (fig. 2.7).30

Last, and possibly most important in thinking about the possible significance of her practice to Girolama’s Accademia portrait, are two large, ambitious, but undated narrative single-sheet woodcuts. The woodcuts, one biblical and one mythological, are both full of figures and made after drawings by Antonio Tempesta. Both are signed with Girolama’s full name instead of a monogram:

-

The Last Judgment, at lower left: HIER[onim].A P[arasol].E INC[idit]. /A[ntonio]TE[mpesta] (fig. 2.8).31

-

Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs, center bottom: HIERONIMA PARASOLIA INCID.; at lower right: ANTO. TEMPEST. Inven. (fig. 2.9).32

Both prints are much larger than the small boxwood blocks Girolama was accustomed to carving, which fit into printers’ frames among the text characters. These are slightly smaller than a sheet of foglio imperiale, and although the few surviving impressions of both prints are cropped close to the image, it is possible to see that there was originally a black border printed around them.33 The size of Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs may be partly responsible for the boldness of its execution, which is difficult to notice properly for the unevenness of the ink distribution over such an expanse of image. The dramatic battle scene features sword-wielding centaurs and mounted soldiers; at the center bottom, over a banner unfurling to proclaim the Latin version of Girolama’s name, a defeated centaur lies crumpled on the ground, his head buried in his folded arm. The melee of men and horses is pure Tempesta, and Girolama has included his name rather proudly as inventor of the image on the strap of a buckler littering the foreground on the right.

There is so much still to know about this woodcut, as remarkable for its obvious ambition as a large, multi-figural battle scene as for having been carved by a woman who signed it front and center, in a gleeful visual proclamation of her role as its carver. While there is no date on the image, the full signature most likely means that Girolama was working alone, after the death of her husband. As a widow in Rome, she could move freely among the protective community of male artists and writers who had provided images for her and her husband to carve, and who had stood as godfathers and employers to their children. Perhaps she had taken note of the high value of her work on the image of Giove Pluvio, and felt confident enough to try printmaking in a different milieu—that of the artist—which would have offered new opportunities for intagliatori who, it was argued, should be considered as practitioners of disegno. The notice of her death in parish records intriguingly calls her a “sculptress and painter.”34 But what did her presence in the form of a portrait add to the intentional history of the Accademia di San Luca and its narrative of the development of the arts in Rome? What was the role model her portrait provided for artists to follow?