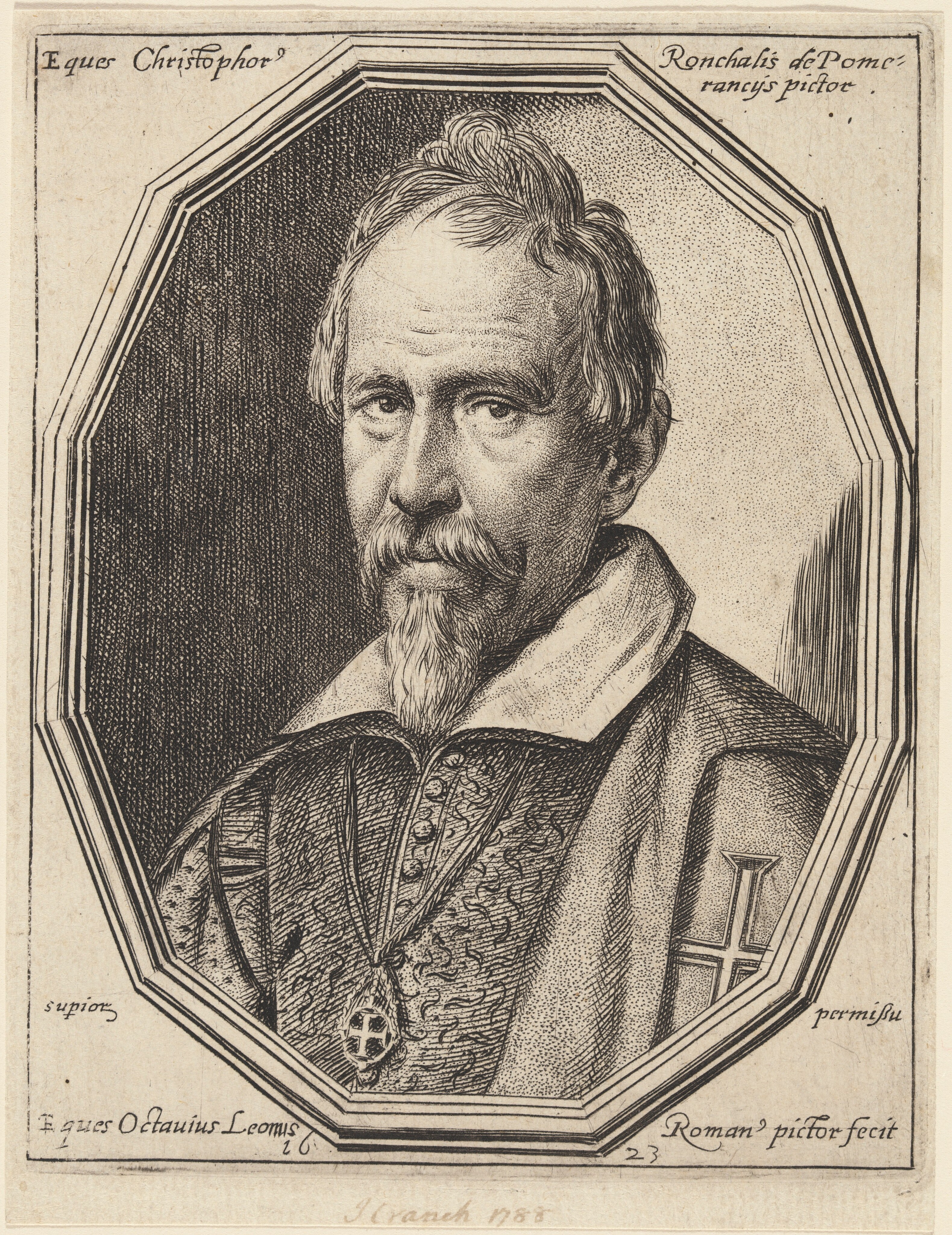

One guiding hand is not usually the case in institutional collections built over many years, but just who was chosen to appear in the Accademia’s gallery of faces must have been a subject of considerable debate at the academicians’ adunanze (meetings). The artists who composed most of these paintings are unknown. According to Baglione, however, Antiveduto Gramatica painted his own portrait, Orazio Borgiani painted Tommaso Laureti’s portrait, and Ottavio Leoni painted Tommaso Salini’s.32 A bound volume of Leoni’s drawings in Florence has six portraits closely resembling those listed in the 1633 inventory: Annibale and Agostino Carracci, Caravaggio, Antonio Tempesta, Cristoforo Roncalli, and Ludovico Leoni.33 From these drawings, Leoni engraved portraits, dating from 1621 to 1625, as for example his print after Roncalli’s portrait (fig. 1.4).34

This suggests that these drawn and printed images were the models from which the painted portraits were composed. Inscriptions on the versos of Michelangelo’s, Dürer’s, Baccio Bandinelli’s, Adam Elsheimer’s and Jacopino del Conte’s portraits read that Leoni donated them in 1616.35 Leoni’s own portrait was not listed on the 1633 inventory, but his stepson, Ippolito Leoni, painted Ottavio’s portrait and donated it in 1633, according to an inscription on its verso.36 Leoni himself as the newly appointed principe had called for the 1627 inventory that listed 58 portraits, perhaps to learn who was already included and who might need to be added. Eleven more were counted six years later. This suggests that Leoni was a driving force behind expanding the Accademia’s portrait collection.37

Principi would have had sway in decision-making. Ottavio Leoni drew, engraved, and then painted a portrait of his father, Ludovico Leoni, which he donated to the Accademia, according to Baglione.38 Verso inscriptions on the portraits of Matthijs Bril and Bernardino Cesari document that their brothers, Paul Bril and Giuseppe Cesari, respectively, donated their portraits in 1622. A verso inscription on Luca Cambiaso’s portrait states that it was donated by Cambiaso’s student, Bernardo Castello, who likely based it on a self-portrait in the Uffizi.39 Understanding how some of these donors’ intentions led to the inclusion of men personally important to them can perhaps illuminate how Parasole—a woman working as a book illustrator in the commercial sphere—could have come to be included. Although not nearly as influential as a principe, Rosato and Bernardino Parasole might have influenced decisions to include a member of their family. Girolama’s brother-in-law Rosato appears in documents as a witness in the Accademia’s administrative meetings: one for the appointment of a procurator and another for the receipt of a payment. Girolama’s son Bernardino had been present at that 1624 meeting in which the principe ordered an inventory of the collection.40 Bernardino’s connections to Giuseppe Cesari and Cristoforo Roncalli make it likely that they would have also spoken in favor of Girolama’s inclusion. And Girolama and Leonardo’s working record of making prints and book illustrations after many of Antonio Tempesta’s images also makes it likely that Tempesta would have spoken on her behalf.41

The only other woman represented in the portrait collection in 1633 was Sofonisba Anguissola (fig. 1.5). However her portrait was mistakenly based on a painting of an unknown woman—a picture that did not portray Anguissola but was painted by her, now found in the Château de Chantilly (fig. 1.6). The error to choose this richly dressed woman as the model for Anguissola’s Accademia portrait discloses how she was perceived by the copyist far away in Rome. Her elegant appearance is somewhat in keeping with her position as a painter at the court of King Philip II. It appears, however, something like the visual equivalent to how Pietro Paolo de Ribera described her in his 1609 biography, saying that she had been courted by Spanish and Italian knights and had dressed as other ladies at court, wearing rich fabrics of gold and necklaces with jewels and pearls. As Julia Dabbs has observed, regularly repeated topoi that male biographers deployed when writing about female artists were not without their own inaccuracies and stereotypes.

Often, for example, they emphasized a female artist’s internal and external virtues, such as her humility or her beauty.42 The Accademia portrait is not at all like Anguissola’s many self-portraits, in which she is often rather austerely dressed and her hair simply arranged. By comparison, Parasole’s middle-aged face is quite un-idealized. Her mouth pulls slightly to one side, composed as if by someone who knew her personally, which is likely given that she lived in a neighborhood filled with artists who would have known her and her family.43

Parasole’s inclusion stands out because her role in the commercial sector as a block cutter for Roman book publishers certainly differed from Anguissola’s success with patrons at court. Indeed the latter’s profession was more in line with the reverent ideals regarding visual art that had been promoted by the Accademia at its founding in 1593. The selling of sacred or profane images in a window or other public place was discouraged.44 The inclusion of these portraits of women artists, who died within three years of each other, convey a type of display attached to their biographies, whether known firsthand to academy members or perceived from a literary or historical distance. Anguissola had been valued for her international fame, and Parasole for her local recognition. Their portraits at the Accademia also rather epitomize the presence of women as accademiche di merito.45 They were included, but were far fewer than the men attending and teaching. From 1607 forward, women, like foreigners, could apply for membership but had no voting rights on school governance.46 It is unknown whether Girolama was a member of the Accademia during her lifetime. Her name has not been found in any other documents, but regardless she would have been banned from participating in administrative meetings, something that makes her inclusion within the Accademia’s portrait collection even more extraordinary: her portrait was displayed as a sign of the esteem in which she was held during the first half of the 17th century.