Premise

The cameral obligation (obligatio cameralis, or in forma Camerae) is a juridical institution that is relatively unknown even to scholars of law, but which was adopted very frequently in the Papal States in the early modern age.1 In fact, in the Papal States, the formula of the cameral obligation was included in all contracts in which there was a financial obligation on the part of at least one of the contracting parties, but it was used in a wider sense in all the cases in which assurance and speed of fulfillment were desired.

A decision of the Rota (chief tribunal of the Holy See) in 1644 maintained that in the Papal States contracts were almost always stipulated with cameral obligations “In Statu Ecclesiastico fere semper stipulantur contractus sub obligatione Camerali.”2 To underline its importance, we can add that the magnificence of Renaissance and baroque Rome was brought about by artists and artisans whose contracts abounded in obligations in forma Camerae.

With regard to art, the extreme relevance of the cameral obligation in regulating the juridical relationship between private individuals, or between private individuals and civic or ecclesiastical patrons, emerges with great clarity. A few examples of published contracts will suffice to illustrate this. Michelangelo Buonarroti was commissioned with cameral obligation to design the tomb of Julius II.3 The same formula was used for Caravaggio’s contracts for work in San Luigi dei Francesi4 and in Santa Maria del Popolo;5 for Nicolas Cordier’s contract for the bronze statue of Henri IV of France in San Giovanni in Laterano;6 and for Peter Paul Rubens’s contract for the high altarpiece of the Chiesa Nuova.7 When it was feared that the dome of the Sapienza was too heavy, Francesco Borromini stood surety pledging the cameral obligation.8

Furthermore, the documents that have been transcribed and digitized for the National Gallery’s research project, The History of the Accademia di San Luca, c. 1590–1635: Documents from the Archivio di Stato di Roma, testify to the frequent use of the cameral obligation in the juridical relationships on which the activity of Roman artists was based.

The Accademia’s statute stipulated that any “imprestanza” (loan, or commodate, which is a gratuitous loan) to the associates had to be formalized with the cameral obligation.9 Many types of obligations were assumed in cameral form: rents, sureties, census, etc. Artists also undertook to pay the tax on evaluations in forma Camerae, paying the Accademia 2 percent of the work’s estimated value. In fact, what the statutes called the Forma della Polliza da farsi & sottoscriversi da quelli che vorranno le stime10 is expressed in the notarial documents as cameral obligation. Among the many examples we have,11 there is that of Guido Reni, who in 1609 promised to render 2 percent of what he was to be paid for his work at the Palazzo Apostolico, which still had to be appraised.12 In 1607 the curate of the church of San Luca, Andrea Glacisco, after having received the inventory of the movable property in the sacristy, undertook with cameral obligation to give an account of said property whenever requested by the Accademia.13 In 1621 the members of the secret congregation pledged in forma Camerae to comply with the brief of Gregory XV, who had confirmed the statutes of the Accademia.14 Furthermore, the deputies of the Congregazione dei Pittori undertook with the cameral formula to celebrate intercessory masses in the church of San Luca.15 There are many more examples that could be cited.

The essay continues with discussion of the following topics: (1) what was the origin and history of the cameral obligation; (2) who had jurisdiction over the cameral obligation; (3) what was the executio parata (forced execution of debt characterized by particular celerity) that the cameral obligation guaranteed and how was it linked to excommunication; (4) what was the role of notaries in the procedure; (5) how was it implemented. To this end we will try to point out the differences between the stylus antiquus of the obligation in forma Camerae (before 1570) and the stylus modernus, adopted exclusively in the documents of the Accademia. Finally, in the conclusion, we will indicate how to recognize the cameral formula in the notarial documents. An appendix will provide a list (not exhaustive) of Accademia documents—contained in the National Gallery of Art’s database—in which the cameral formula is given in abbreviated form.

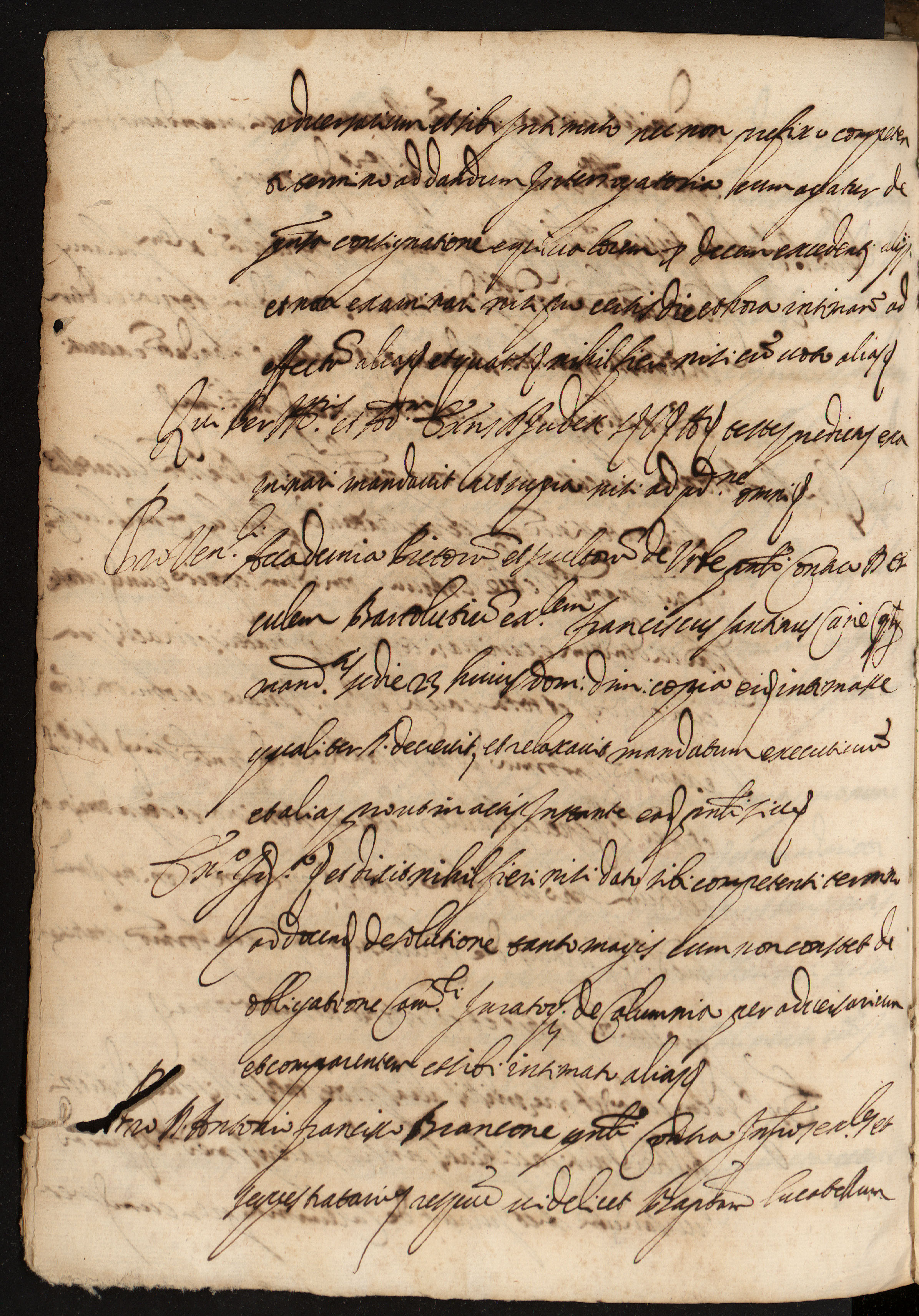

Header image: Archivio di Stato di Roma, TCS, Vol. 0551, 1637, fol. 387v (detail)